bguspl

Thread Safety: Locks and Atomic Operations

In the last lecture we discussed immutability as a way to guarantee the safety and correctness of our classes. During this lecture, we continue with synchronization mechanisms modern RTEs offer us to cope with concurrency issues.

Java Basic Synchronization - Monitors

The most basic mechanism Java offers the programmer to facilitate the safety of concurrent objects is called synchronization. Think of two threads which try to access the same object concurrently. To preserve the safety of the object, those two (or more) threads need to synchronize their access to the internal state of the object. For example, consider the (mutable) class Even from the previous lecture:

class Even {

/* the internal state counter

* @INV counter % 2 = 0

*/

private int counter = 0;

/* increment the counter.

* return the updated counter value

* @PRE counter % 2 = 0 (this is redundant, as it is promised by the @INV)

* @POST @POST(counter) = @PRE(counter)+2

*/

public int add() {

counter += 2;

return counter;

}

}

If two threads can manipulate the internal state of such an object concurrently, the safety of the object is compromised, as we saw in the previous lecture. This means that the state of the object can end up not satisfying the @invariant of the class when run in a concurrent environment, even though the code would be perfectly safe when run in a sequential environment.

Java offers a mechanism through which we can coordinate the actions both of these threads perform on the object. For example, if we could express in Java that only one thread is allowed to enter the add() function of the same object at a time, we can then ensure that the safety of the object will be preserved.

Java provides native support for the concept of monitors - but before we can understand what monitors are and how they can help us solve similar problems like we saw before we will need to introduce two more problems that araise when using shared resources by different threads - the problems of memory visibility and instruction reordering.

Memory Visibility and Instruction Re-ordering

We will start by introducing the problem of Memory Visibility, Visibility determines when threads can see values (of all types, even references to objects) written to memory by other threads. Consider the following code:

class Work {

boolean done = false;

void work() {

while (!done) {

System.out.println("I am working la la la!");

}

}

void terminate() {

done = true;

}

public static void main(String[] args) throws Exception {

Work w = new Work();

Thread worker = new Thread(w::work);

worker.start();

Thread.sleep(1000);

w.terminate();

worker.join();

}

}

In this code, the worker thread may never stop - as it may never see the update to done performed by the main thread. In practice, this may happen if the compiler detects that no writes are performed to done in the first thread; the compiler may decide that the program only has to read done once, transforming it into an infinite loop.

It is important to understand that “compiler” in this context doesn’t mean javac — it actually means the JVM itself, which plays lots of games with your code to get it to run more quickly. In this case, if the compiler decides that you are reading a variable that you don’t have to read, it can eliminate the read quite nicely. As described above.

Let us now continue to show another problem - Instruction reordering: Reordering is what happens when the compiler and the RTE change our code behind our back, to better optimize it1. For example, the compiler may decide to convert the following code:

int i=10;

int b=11;

i++;

b++;

into this code:

int i=10;

int b=11;

....

....

b++;

i++;

The compiler must be able to re-order simple instructions to optimize our code. It would do that only if there is no “must-happen-before” constraint on the code being reordered.

If there was a “must-happen-before” constrain in our example then the compiler would not reorder it. For example:

int i=10;

int b=11;

....

....

i++;

Print (i)

b++;

In fact “must-happen-before” constrained would happen just because we call any other (non-inline) function in the middle since the compiler would not go recursively into that function to see what it is doing:

int i=10;

int b=11;

....

....

i++;

NonTrivialFunc();

b++;

The compiler only guarantees safe reordering in a non-concurrent execution environments. However, in concurrent environments, reordering may harm us.

Java monitors (and the “synchronized” keyword)

Lets start with an example of using monitors in order to solve our problem and then we will attempt to understand what we actually did. Consider the following code:

class Even {

private int counter = 0;

public int add() {

synchronized(this) {

counter = get() + 2;

return counter;

}

}

public int get() { synchronized(this) {return counter;} }

}

Notice the synchronized block used inside the add() and get functions. The synchronized block must include a non-null object (this in our case). the Java RTE (a.k.a., the JVM) ensures that, during runtime, only one thread at a time may access a synchronized block of the same object (this in our case). Moreover, synchronization also solves the visibility and reordering problems; a “write” to a memory location which takes place during a synchronized code section is guaranteed to be returned to all “read” operations following it, if they are synchronized on the same object. Another important thing to notice is that if a thread which already entered a synchronized block that belongs to this for example in the add method it can enter any other synchronized block that of “this” without waiting e.g., the one inside the get method.

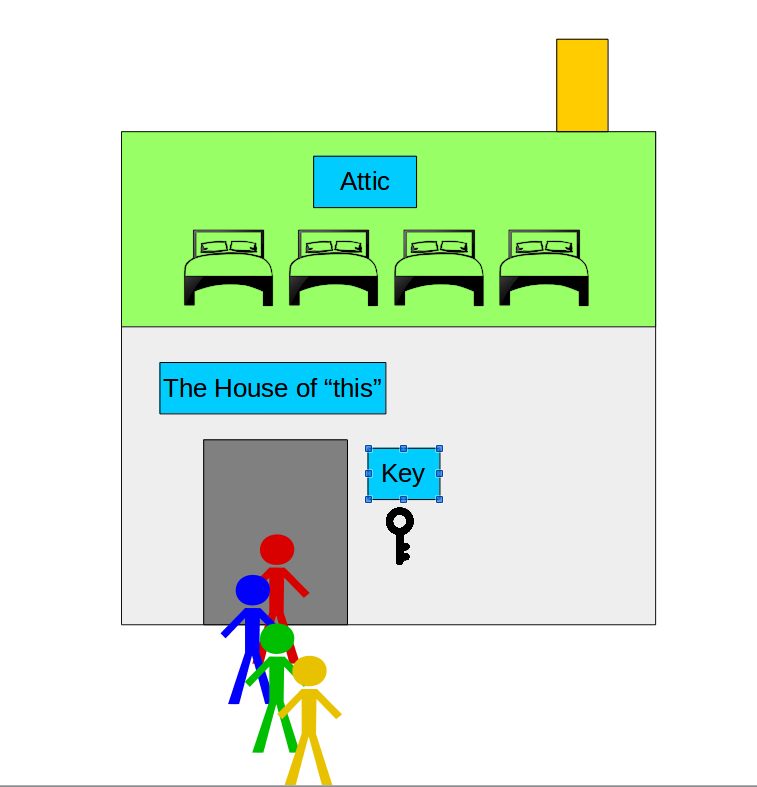

In order to understand better, we can imagine that each object in java has a house, the house has only one key and when a thread enter the house it takes that key with him. Using this key, the thread can enter any room in the house (=reenterant). While the key is held by another thread - other threads that want to enter the house must wait until the key will became available (=mutex). Once a key becomes available - all threads attempt to take it - no matter who came first (=non-fair) - but only one of them will succeed and enter the house - while the others will be forced to wait again.

The figure above illustrates a synchronization on this, notice the “attic” part - we will discuss it later.

It is common to synchronize whole instance methods on the this object (like the add and get methods we saw) and therefore there is a “shortcut” for this in java, i.e., the code above can be written like this:

class Even {

private int counter = 0;

public synchronized int add() {

counter = get() + 2;

return counter;

}

public synchronized int get() { return counter; }

}

Notice that the keyword synchronized is added on an instance method which just means to synchronize the whole method block over the lock belongs to the this object.

Next, we will elaborate on the mechanism Java employs, internally, to enable such synchronization. Understanding this mechanism will help us use it to better effect and avoid common pitfalls.

How “synchronized” is implemented

Each object inside the JVM (at runtime) has an associated monitor (the “house” that we saw earlier). The JVM is in charge of maintaining and initializing these monitors. The JVM attaches such a monitor to every object in the system, such that each object has a monitor all of its own. We, as programmers, cannot access these monitors explicitly (they are not standard members of any class), rather we can employ them implicitly by using the synchronized keyword.

Monitors may be in one of two states; either in the possession of a thread or available. A thread, T, may try to acquire the monitor of any object. If the monitor is available, the lock is immediately transfered into the possession of T. Otherwise, T goes to sleep until the monitor is available (this happens when the thread that currently possesses the monitor releases it). Then T wakes up and tries to acquire the monitor again (T may fail again, as another thread may have been quicker and grabbed the monitor before T woke up).

When we declared the add() method as synchronized, the compiler added something like the following pseudo code to the method:

public synchronized int add(){

takeMonitorIfNotAlreadyPossessIt(this);

try {

counter = get() + 2;

return counter;

} finally {

// note that a finally block is executed even if there is a return inside the try

releaseMonitorIfNotNeededByCallingFunction(this);

}

}

As can be seen in the code snippet above, each thread, when trying to call the method, must first try to acquire the monitor. Moreover, when the thread exits this function, the thread will release the lock if it is not needed anymore.

The cost of this implementation

Using synchronized comes with a price. To ensure correct memory semantics, before a thread enter a synchronized block and after it exits the synchronized code block all its memory needs to be synchronized with the main memory. Since each thread may cache copies of the main memory in its own memory (e.g., in CPU registers or on a CPU cache closer to the thread). This is a costly operation.

The other cost, is that as long as a thread is active in the body of a synchronized block for a certain object, all other threads that attempt to acquire the monitor of the same object will have to wait.This means that threads must wait for each other - if this happens a lot, then the program became serial or mostly serial and the benefits of multi-threading vanishes.

When to Use Synchronization

Essentially, we want to use synchronization when we find a piece of code that we want to be atomic . An operation is atomic if its result seen to happen ``all at once’’. Using monitor synchronization will: (a) allow only one thread to enter a synchronized block of the same monitor, (b) solve the reordering problem - as the operation seem to happen “all at once” there cannot be ordering problems, (c) solve the memory visibility problem by “flashing” the local thread memory (e.g., registers) before entering a synchronized block and after exiting.

But synchronization is something you should aspire to avoid as much as possible as it makes your code less parallel. At some cases using synchronization can even make your code slower than sequential execution as you must execute more code in order to manage multiple threads without actually benefit anything. If you cannot avoid synchronization you should at least try to synchronize only small parts of code and use different monitors for unrelated code blocks.

Synchronized Properties

There are some language rules to which we must adhere when using synchronization and some miscellaneous issue which must be observed.

- The

synchronizedkeyword is not part of the method signature. - The

synchronizedkeyword cannot be specified in an interface. - Constructors may not be declared as ```synchronized`` (There would be no point in declaring a constructor synchronized, since as long as the constructor is not complete, the object instance is not yet accessible by any other thread than the one constructing it.)

- When we declare a static method as

synchronized, we are actually telling the JVM that, in contrast to a regular method where we ask that the lock associated with the object be used, we want the lock associated with the class to be used. This is possible since each class in Java is also an object on its own. - Java locks are Reentrant: The same thread holding the lock can get it again and again.

Partially synchronized objects

In case we identify disjoint groups of methods in a given class, which access disjoint parts of the object state (=different fields), we can synchronize the methods of each group on its own lock object. This will enable concurrent computation of methods of disjoint groups.

The class Point for example, which defines the coordination of a given point in a two-dimensional space, contains one group of methods - left, right, getX - which access the _x field, and another group of methods - up, down, getY - which access the _y field. Synchronizing each group on its own lock object will allow concurrent application of up/down/getY and left/right/getX.

class Point {

private long _x, _y;

private Object _lockX, _lockY;

Point(int x, int y) {

_x = x;

_y = y;

_lockX = new Object();

_lockY = new Object();

}

public void up() {

synchronized(_lockY) { _y++; }

}

public void down() {

synchronized(_lockY) { _y--; }

}

public void left() {

synchronized(_lockX) { _x--; }

}

public void right() {

synchronized(_lockX) { _x++; }

}

public long getX() {

synchronized(_lockX) { return x; }

}

public long getY() {

synchronized(_lockY) { return y; }

}

}

Design Patterns to Enforce Safety

Lets create a simple “thread safe” linked list

public class LinkedList<T> {

private Link<T> head = null;

public synchronized void add(T data) {

head = new Link<>(head, data);

}

public synchronized boolean contains(T data) {

Link<T> l = head;

while (l != null) {

if (l.data.equals(data)) {

return true;

}

l = l.next;

}

return false;

}

private static final class Link<T> {

private Link<T> next;

private T data;

public Link(Link<T> next, T data) {

this.next = next;

this.data = data;

}

}

}

Now let us consider the following code:

class Example {

public void doSomething(LinkedList<Integer> l) {

if (!l.contains(42)) {

l.add(42);

}

}

}

Is the doSomething function “thread safe”? Probably not (life is just not fair).

The reason is that after calling the l.contains method some other thread may add 42 to our list and then doSomething will add another one..

Is this solve the issue?

class Example {

public synchronized void doSomething(LinkedList<Integer> l) {

if (!l.contains(42)) {

l.add(42);

}

}

}

The solution presented above is incorrect. The reason is that the lock protecting the doSomething() method is different from the lock protecting the add().

One solution to this problem is to go and add a new method: addIfAbsent to our LinkedList and synchronize it, but what if we dont have the code of LinkedList or we cannot change it?

There exist two design patterns which can help us solve this issue. Each one is relevant in slightly different circumstances: Composition and Client Side Locking.

Composition (also named Containment) is about wrapping our LinkedList class in a new class while exposing all the original LinkedList methods and adding new ones that we need, e.g.,:

class BetterLinkedList<T> {

private LinkedList<T> delegate = new LinkedList<T>();

public synchronized void add(T data) { delegate.add(data); }

public synchronized boolean contains(T data) { return delegate.contains(data); }

public synchronized boolean addIfAbsent(T data) {

if (!contains(data)){

add(data);

return true;

}

return false;

}

}

As seen in the example, Composition (also named Containment) is about wrapping a class and re-exposing most or all of its functionality. Why not extend the LinkedList class and add the function we want? The answer is that we do not always know how the class LinkedList protects itself from concurrent access. Specifically, we do not know, and may not have access to, which objects are used by the LinkedList class to synchronize access to itself. Moreover, it is a good design strategy to have a basic (non thread safe) object and a thread safe version of it.

Client Side Locking Sometimes we may know the identity of the object which is used for synchronization. For example, we may know that the LinkedList class uses its own monitor (lock) to achieve synchronization. We can then use the following implementation:

class Example {

public void doSomething(LinkedList<Integer> l) {

synchronized(l) {

if (!l.contains(42)) {

l.add(42);

}

}

}

}

Client side locking may be used only when we know the internal implementation of the object we are using. In our example, we know that the class LinkedList protects itself by using its own monitor, such that we can use the same monitor (the LinkedList object itself) to perform thread-safe operation. Client side locking is not appropriate when we either do not know the internal implementation or the implementation may change in the future.

In general, client-side locking is NOT a good idea: it gives the responsibility of synchronization to the clients instead of centralizing it in the object we want to access. The problem is then: how can we insure consistency among ALL the clients that access this object? If one of the client does not synchronize correctly, then ALL the code will behave incorrectly. It is always better to enforce safety on the provider side, not on the client side.

Version Iterators

Lets now say that we want to be able to iterate over our list so we modify it as follows:

public class LinkedList<T> implements Iterable<T> {

private Link<T> head = null;

public synchronized void add(T data) { ...

public synchronized boolean contains(T data) { ... }

public Iterator<T> iterator() {

return new Iterator<T>() {

Link<T> cur = head;

@Override

public boolean hasNext() {

return cur != null;

}

@Override

public T next() {

T data = cur.data;

cur = cur.next;

return data;

}

};

}

}

now we can use our code as follows:

public void printList(LinkedList<Integer> l) {

for (Integer i : l) {

System.out.println(i);

}

}

BUT what will happen if while executing printList some other thread will add or remove an item from l? depending on the implementation this can cause many problems.

So what can we do?

The first and easiest solution is to first create a temporary copy of the LinkedList, and then iterate over this copy, which is local to the current thread. However, there are still several problems with this; (a) it may be inappropriate to copy the entire data structure, as it may incur a large computation overhead and (b) we still need to iterate the LinkedList in order to copy it - so back to square one..

A better solution is a fail-fast iterators - which are iterators that detect that a change to the data structure happened while they are in use and throw an exception in order to indicate that they are inappropriate for usage any more.

So how we can change our iterator to fail-fast? we need a way to detect a change in the LinkedList. A nice design pattern that can help us with it is the version iterator - It is pretty self explanatory:

public class LinkedList<T> implements Iterable<T> {

private Link<T> head = null;

private int version = 0;

public synchronized void add(T data) {

head = new Link<>(head, data);

version ++;

}

public synchronized boolean contains(T data) { ... }

public Iterator<T> iterator() {

return new Iterator<T>() {

Link<T> cur = head;

int iver = version;

@Override

public boolean hasNext() {

return cur != null;

}

@Override

public T next() {

synchronized (LinkedList.this) {

if (iver != version) throw new ConcurrentModificationException("version changed!");

T data = cur.data;

cur = cur.next;

return data;

}

}

};

}

}

More Synchronization Primitives

The Java concurrent package introduces high-level concurrency primitives.

The Lock interface in Java introduces a key functionality: the possibility to test that a lock can be acquired without blocking. Lock objects work like the implicit locks used when accessing a synchronized code segment. Only one thread can own a Lock object at a time. The biggest advantage of Lock objects over implicit locks is their ability to back out of an attempt to acquire a lock: The tryLock() method returns if the lock is not available immediately or before a timeout expires (if specified).

- Semaphore

- Exchanger

- Latch

Guarded Methods and Waiting

Traditionally, in sequential programming - methods refuse to perform actions unless they can ensure that these actions will succeed, in part by first checking their preconditions. For example, let us add a removeFirst method to our LinkedList:

public class LinkedList<T> {

private Link<T> head = null;

public synchronized void add(T data) {...}

public synchronized boolean contains(T data) { ... }

public synchronized T removeFirst() {

if (head == null) throw new IllegalStateException("list is empty");

result = head.data;

head = head.next;

return result;

}

}

The method checks first to see that the list is not empty and throw exception if it is. Unlike sequential code, multi-threaded code have other alternatives in how to handle unfulfilled pre-conditions, in general, there are three basic flavors of policy decisions surrounding failed preconditions/invariants:

-

Balking. Throwing an exception if the precondition fails. Here, an exception indicates refusal, not failure, but they have the same consequences to clients. This is what we do in the code above.

-

Guarded suspension. Suspending the current method invocation (and its associated thread) until the precondition becomes true.

-

Time-outs. Cases falling between balking and suspension, where an upper bound is placed on how long to wait for the precondition to become true.

You already know about Balking, but what is Guarded suspension?

Guarded Suspension

Guarded suspension and time-outs have no analog in sequential programs, but play central roles in concurrent software. The main idea of Guarded Suspension is that the thread will wait (Suspended) until the pre-condition holds.

Guards can be considered as a special form of conditionals. In sequential programs, an if statement can check whether a condition holds upon entry to a method. When the condition is false, there is no point in waiting for it to be true – it can never become true since no other concurrent activity may cause the condition to change.

For example, in our LinkedList’s removeFirst implementation, if we found that the linked list is empty we can choose to wait for it to get field instead of throwing an exception:

public class LinkedList<T> {

private Link<T> head = null;

public synchronized boolean contains(T data) { ... }

public synchronized void add(T data) {

head = new Link(head, data);

notifyAll();

}

public synchronized T removeFirst() {

while (head == null) wait();

result = head.data;

head = head.next;

return result;

}

}

We are introduced here to two new functions that are part of the Java API: notifyAll and wait, there is another relevant function which is notify. In the following we will attempt to fully understand what they does.

Java Mechanics for Guarded Suspension

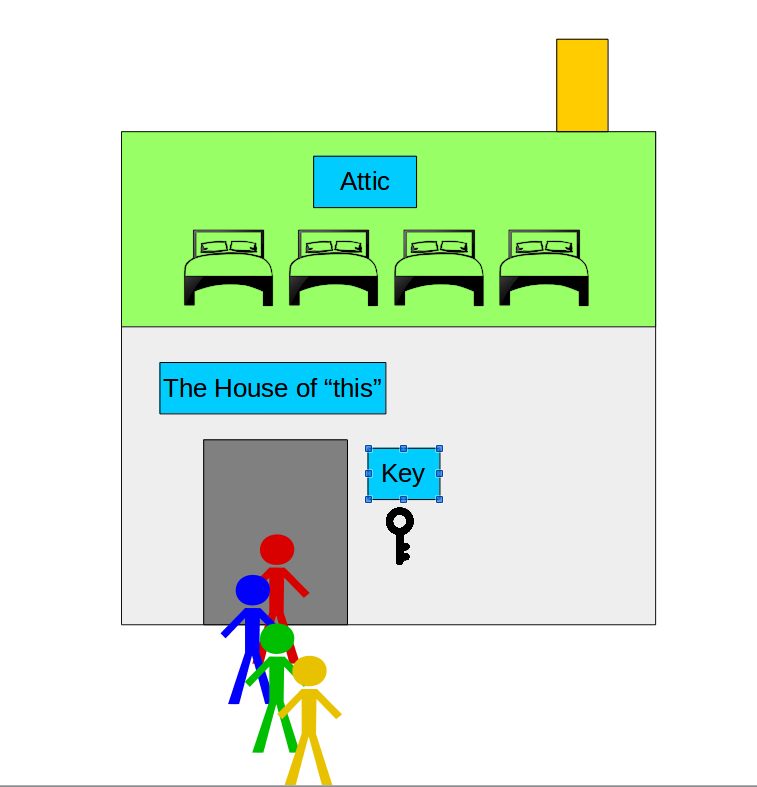

The Java RTE offers the programmer a simple mechanism to facilitate guarded suspension and suspension in multi-threaded context in general, the wait and notify constructs. Recall the figure which was used to describe a monitor:

We can use this figure again in order to understand how wait and notify works. When a thread enter the house (monitor) it allowed to do the following:

- Enter the attic and sleep there by calling the wait function on the object that the monitor belongs to. Before going to sleep in the attic, the thread will first return the key back to its place - so that other threads can now enter the house.

- Wakeup one or all the threads that sleep in the attic (

notify/notifyAll) once a thread is woke up - it must go down, exit the house and wait like all the other threads for a key to become available before re-entering the house.

To be more formal, the “attic” is called the monitor “Waiting Set”, a call to wait insert the calling thread to the waiting set and release the monitor. A call to notify chose arbitrary thread from the waiting set, once the thread will be able to acquire the monitor again - it will continue from where it was stopped. A call to notifyAll just release the whole waiting set.

Common pitfalls - guard atomically

In the LinkedList code we saw above we may notice that the wait function is called inside a loop, can we replace this loop with an if?

public class LinkedList<T> {

private Link<T> head = null;

public synchronized boolean contains(T data) { ... }

public synchronized void add(T data) {

head = new Link(head, data);

notifyAll();

}

public synchronized T removeFirst() {

if (head == null) wait();

result = head.data;

head = head.next;

return result;

}

}

This code will not work as it not fulfill a property which is called the guard atomically property:

Consider the following scenario, in which there are two Consumer threads and one producer. The list is empty at first, and both of the consumers execute the removeFirst() method. Both of the consumers will block (i.e, wait). Now comes along a single producer, which calls add() once. Since the producer calls notifyAll(), both of our consumers will wake up. Now, both of them (in some order) will execute the body of the remove method. This is a problem, as the precondition does not hold for at least one of them.

What if we are sure that there is only one consumer thread? can we replace the while with an if then? Sadly no - because of a scenario that is called a “spurious wakeup*.

Spurious wakeups describes a complication that exists in the implementation of the functionality that is provided by the OS and is used in order to implement monitors (note that this is not specific to java). Without getting too technical - a spurious wakeup describes a scenario where a “waiting” thread is wokeup without any other thread calling to notify or notifyAll. Since Java uses the operating system threads underneath - it is vulnerable to spurious wakeups and therefore we must use the while loop.

Common pitfalls - wait atomically

In the previous sections we emphasis that if using synchronization you should synchronize the smallest possible code blocks - taking this into consideration, will the following code work?

public class LinkedList<T> {

private Link<T> head = null;

public synchronized boolean contains(T data) { ... }

public synchronized void add(T data) {

head = new Link(head, data);

notifyAll();

}

public T removeFirst() {

while (head == null) synchronized(this) {wait();}

synchronized (this) {

result = head.data;

head = head.next;

return result;

}

}

}

Notice that we reduce synchronization and only synchronized when actually modifying the list or attempting to wait. Sadly, this code will not work as it does not has a property called the Wait atomicity property:

Consider a scenario in which there are exactly one producer and one consumer. The first to run is the consumer, which calls the removeFirst() method. The consumer checks the condition, but is stopped right after (by the scheduler). Now comes along the producer and calls add() successfully. Note that the producer invoked the notifyAll() method of this, however there was no thread in the wait set in that time! Now, the consumer is resumed (again, by the scheduler) and calls this.wait(). But the queue is not empty now! The consumer missed the notification.

Rules of Thumb for Wait and Notify

-

Guarded wait - For each condition that needs to be waited on, write a guarded wait loop that causes the current thread to block if the guard condition is false.

-

Guard atomicity - Condition checks must always be placed in while loops. When an action is resumed, the waiting thread doesn’t know whether the condition it is waiting for is actually true; it only knows that it has been woken up. Thus, in order to maintain safety, it must check again. Even worst, in rare cases a thread can also wake up without being notified, interrupted, or timing out, a so-called spurious wakeup. Checking the condition in a loop ensures it would cost no harm.

-

Multiple guard atomicity - If there are several conditions which need to be waited for, place them all in the same loop.

-

Don’t forget to wake up - To ensure liveness, classes must contain code to wake up waiting threads. Every time the value of any field mentioned in a guard changes in a way that might affect the truth value of the condition, waiting threads must be awakened so they can recheck guard conditions.

-

notify()Vs.notifyAll(): when multiple threads wait in the same wait set of a single object, such that there are at least two threads waiting for different conditions, we must usenotifyAll()to ensure that no thread misses an event. For example, consider a simple queue which has both anadd()method, as above, and anaddTwo()method, which adds two objects into the queue at the same time. Now, threadt_1may be waiting for the queue to empty out in the add method, checking that there is at least room for one object, and threadt_2may be waiting in theaddTwo()method, checking that there is place for two objects. Now, consider that theget()method callsnotify(), and the thread which gets woken up ist_2. Alas, there is only room for one object in the queue, sot_2goes back to sleep. Moreover,t_1will not be woken up at all, even though there is space in the queue.

More Sophisticated Primitives

Wait and Notify are the basis for higher level constructs. While Wait and Notify are very general constructs, other, more specific mechanisms can make your code easier to understand and demand less details when using them. We review here Semaphores and Readers-Writers locks.

java.concurrent.BlockingQueue

A queue that support blocking if there are no elements in the queue, it has two implementations: LinkedBlockingQueue is based on a linked list and ArrayBlockingQueue is based on an array, the later also support blocking if attempting to add while the internal array is full.

Semaphores

A Semaphore is an abstraction of an object which controls a bounded number of permits. A permit is an abstract concept, which we can think of as a train ticket. Threads may ask the semaphore for a permit (a ticket). If the semaphore has any permits available, one permit will be assigned to the requesting thread. If there is no permit available, the requesting thread is blocked until one such permit exists – for example, when another thread returned the permit it received at an earlier stage.

For example, say that we want to have a code that is allowed to be executed by no more than 2 threads at once we can implement it as follows:

public class TwoAllwed {

private Semaphore sem = new Semaphore(2);

public boolean doSomething() throws InterruptedException {

sem.acquire();

try {

//do something

}finally {

sem.release();

}

}

}

You should read more about semaphores by looking at the Semaphore API.

You may consider the following (very simple) implementation (this code is only shown for explanatory purposes):

class Semaphore {

private final int permits_;

private int free_;

public Semaphore(int permits) {

permits_ = permits;

free_ = permits;

}

// @PRE: free_ > 0 (There is an available permit)

// @POST: free_ = @pre(free_) - 1

public synchronized void acquire() throws InterruptedException {

while (free_<=0)

this.wait();

free_ --;

}

// Try acquiring a permit if possible without blocking.

public synchronized boolean tryAcquire() {

if (free_ <= 0)

return false;

free_ --;

return true;

}

// @POST: free_ = min(permits_, @pre(free_) + 1)

public synchronized void release() throws InterruptedException {

if (free_ < permits_) {

free_++;

this.notify();

}

}

}

Usage:

class Even {

int val;

Semaphore sem;

Even(int val) throws Exception {

if (val % 2 != 0)

throw new Exception(…);

this.val = val;

this.sem = new Semaphore(1);

}

public int get() {

sem.acquire();

int ret = val;

sem.release();

return ret;

}

public void next() {

sem.acquire();

val++;

val++;

sem.release();

}

}

The following version implements fairness:

class FairSemaphore {

List<Thread> waitingForLockThreads;

Semaphore(int permits) { this.permits = permits; this.free = permits;

waitingForLockThreads = new LinkedList<Thread>();

}

public synchronized void acquire() { // implementation of lock

waitingForLockThreads.add(Thread.currentThread());

while (free <= 0 || waitingForLockThreads.get(0) != Thread.currentThread())

wait();

free--;

waitingForLockThreads.remove(0);

if (free > 0)

notifyAll();

}

public synchronized boolean tryAcquire() {

if (free <= 0 || waitingForLockThreads.size() > 0)

return false;

free--;

return true;

}

public synchronized void release() { // implementation of unlock

if (free < permits)

free++;

notifyAll();

}

}

Readers/Writers Example

The readers/writers problem is about allowing several readers and writers to access a shared resource under different policies. Different policies (variants of the problem) exist. In our example, several readers can access the resource together (to read it), but only one writer can access the resource at any given time. So for example, Readers will wait if any writer is pending (new data is about to be added, so wait for it first). Only one writer at a time can access the shared resource, and only if no readers are currently reading from it.

The mechanism of reader/writer is available in the java.concurrent package in the form of the java.util.concurrent.locks.ReadWriteLock interface and ReentrantReadWriteLock implementation. This lock allows multiple threads to read a certain resource, but only one to write it, at any given time.

This is how ReadWriteLock is used:

ReadWriteLock readWriteLock = new ReentrantReadWriteLock();

readWriteLock.readLock().lock();

try {

// multiple readers can enter this section as long as no writer is waiting or writing.

} finally {

readWriteLock.readLock().unlock();

}

readWriteLock.writeLock().lock();

try {

// only one writer can enter this section, only if no threads are currently reading.

} finally {

readWriteLock.writeLock().unlock();

}

In the following implementation, several readers can access the resource together (to read it), but only one writer can access the resource at any given time. So for example, Readers will wait if any writer is pending (new data is about to be added, so wait for it first). Only one writer at a time can access the shared resource, and only if no readers are currently reading from it.

public abstract class RW {

protected int activeReaders_ = 0; // threads executing read_

protected int activeWriters_ = 0; // always zero or one

protected int waitingReaders_ = 0; // threads not yet in read_

protected int waitingWriters_ = 0; // same for write_

protected boolean allowReader() {

return waitingWriters_ == 0 && activeWriters_ == 0;

}

protected boolean allowWriter() {

return activeReaders_ == 0 && activeWriters_ == 0;

}

public synchronized void readLock() {

++waitingReaders_;

while (!allowReader())

try { wait(); } catch (InterruptedException ex) {}

--waitingReaders_;

++activeReaders_;

}

public synchronized void readUnlock() {

--activeReaders_;

notifyAll(); // Will unblock any pending writer

}

public synchronized void writeLock() {

++waitingWriters_;

while (!allowWriter())

try { wait(); } catch (InterruptedException ex) {}

--waitingWriters_;

++activeWriters_;

}

protected synchronized void writeUnlock() {

--activeWriters_;

notifyAll(); // Will unblock waiting writers and waiting readers

}

}

Note this code handles only the locking while the actual access to the resource is done in a subclass. Also note that the policy of the sharing is determined in two simple methods: allowReader() and allowWriter(). This interface nicely encapsulates our concurrency policy in re-usable code.

Usage:

class Even {

int val;

ReaderWriter rw;

Even(int val) throws Exception {

if (val % 2 != 0)

throw new Exception(…);

this.val = val;

this.rw = new ReaderWriter();

}

public int get() {

rw.readLock ();

int ret = val;

rw.readUnlock ();

return ret;

}

public void next() {

rw.writeLock();

val++;

val++;

rw.writeUnlock();

}

}

Atomic Instructions

Most CPU operations (like add, mov etc.) are atomic - i.e., the instruction result can be seen as if it “happened at once”. We only need to use synchronization if we want several such instructions to be atomic. Most CPUs today offers a set of atomic instructions that designed for multi-threading - an important one is compare-and-set or CAS. CAS is an instruction that behaves as follows:

boolean cas(int target, int oldValue, int newValue) {

if (target == oldValue) {

target = newValue;

return true;

}

return false;

}

The cas instruction is atomic which means that threads sees its result as if it happens at once - in other words - the scheduler cannot stop a thread in the middle of this operation - only before or after it.

Although it does not look like one, the cas instruction is extremely useful and powerful. Java has several classes (all beginning with Atomic* that allow us to use cas). To understand its power, lets rewrite the Even counter class using AtomicInteger:

class Even {

private AtomicInteger counter = new AtomicInteger(0);

public int add() {

int val;

do {

val = counter.get();

}while (!counter.compareAndSet(val, val + 2));

}

public int get() { return counter.get(); }

}

Lets revise the code above:

-

AtomicIntegeris a class that holds integer that we can call cas on (i.e., it will be the target of thecas) -

There is no usage of

synchronizedanywhere in the class. -

if there are n threads

t_1,...,t_nthat attempt to invoke add one time all at once then, without the loss of generality:t_1will enter the while loop once,t_2at most twice, andt_nat most n times. -

This code run significantly faster than the synchronized one as we do not send a thread to sleep (i.e., invokes a system call) whenever a concurrent access is happen

This kind of implementation is called lock-free. Basically, if threads cannot not block each other inside the data-structure implementation, the implementation is called - lock free.

Can we create a lock-free implementation for data structures that require operations that are more complex than adding two numbers? YES, in many cases the basic idea stays the same, copy the cas target to a local variable, change this variable locally, try to commit your change using cas, if failed, retry - this is it!. Lets see another example and implement our linked list lock-free:

public class LinkedList<T> {

private AtomicReference<Link<T>> head = new AtomicReference(null);

public void add(T data) {

Link<T> localHead;

Link<T> newHead = new Link<>(null, data);

do {

localHead = head.get();

newHead.next = localHead;

} while (!head.compareAndSet(localHead, newHead));

}

}

Again this implementation use no locks, it is faster and more efficient.

An important note! while lock free data structures seems better than lock based structures they also has their limitations:

- Since there are no locks, lock-free data structures cannot block threads which may be a required property of the data structure - like for example blocking queues.

- Lock-Free data structures are notoriously known of being much harder to write correctly

- There are some cases where the state of the data-structure may be complex and may require a lock-free implementation that need to copy (to local variables) large amount of data - which may not always be possible or may lead to poor performance.

In other words, in programming - there is no silver bullet - you need to master many different techniques and choose the one that is most suitable to your task. In addition, like most other techniques we learn about in this lecture java has some pre-made implementation for us to use - some useful examples of such are ConcurrentHashMap and ConcurrentLinkedQueue which you can read more about via their APIs javadoc.

An imperfect example of a generic lock-free synchronization

The implementation of lock-free data structures can be tricky to implement. One approach that may seem generic and easy is the following:

public class MyClass {

private AtomicBoolean lock = new AtomicBoolean(false);

public void foo(...) {

while !lock.compareAndSet(false,true);

// Some code goes here...

...

...

...

lock.set(false);

}

}

And in the case of class Even, we may use

class Even {

private volatile int val;

private final AtomicBoolean lock;

Even(int val) {

this.val = val;

this. lock = new AtomicBoolean(false);

}

public int get() { return val; }

public void next() {

while (!lock.compareAndSet(false,true));

val += 2;

lock.set(false);

}

}

The code above is not really “lock-free”, as it locks the awaiting Threads in the while loop in busy-wait mode. We now distiguish between two aspects of lock-free synchronizations:

-

Using

synchronized, threads go to a blocked state, which may be wasteful if the code is short and simple. In lock-free implementation, we aim to prevent these frequent changes in the state, and keep the Threads running. -

In the previous specific lock-free examples, the Threads are not blocked and run the code in parallel, except for the final assignment. This improves the performance, since the final assignment is not limited to one specific thread - only to the first one to complete the code.

The last “generic” example fulfills the first aspect, but not the second one. It is suitable only when the “right” lock-free synchronization is impossible (i.e. the state change depends on more than one assignment), and the code is short. If the code is long, it is better to use the synchronized mechanism instead of the generic lock-free implementation.