bguspl

Memory Management: Stack, Heap and Garbage Collection

Objectives

This lecture initiates our discussion of memory usage. Memory is one of the central shared resources in a multiprocessing RTE. During the discussion we introduce the memory models that are used in Java and C++ programming languages, and the corresponding services that a Java/C++ programmer can get from the underlying RTE (JVM or Operating System).

Different Perspectives of Memory Services

We can look at memory operations at different levels:

- Hardware level: operations like READ and WRITE.

- Operating System level: sharing of the physical memory among different processes, allocating memory to processors, etc.

- Programming Language: how programming language constructs relate to memory operations at runtime and at compile time.

We start with a short background review of memory technologies, continue with an overview of hardware level aspects and finally focus on the programing language aspect.

Background: Memory Technologies

Computer systems are built around different types of memory technologies:

- On-chip storage - registers and cache storage - very fast storage which generally reside on the same chip as the main processor

- Random Access Memory - a family of technologies used to implement the computer main memory the RAM.

- Persistent online storage - Hard disk or solid state disks (SSD) using magnetic or electromagnetic technologies. Persistent offline storage - Tapes/DVD/CD are magnetic or optical offline storage technologies.

There is a natural memory hierarchy used in computer systems: faster memory is available in smaller quantities, slower memory is available in larger quantities. Memory costs rise the faster the memory (access wise) is.

The following properties characterize the memory system of a computer:

- Memory space: how much main memory the processor can address (maximum potential size)

- Word size: words are the native units of data the CPU operates on. Usually, internal registers can store exactly one word, and writes/reads from main memory are at least word-sized.

These 2 parameters correspond to 2 hardware parameters:

- Width of the address bus: memory is viewed as an array of words. Each word has an index (0, 1, …, up to the size of the memory space). The index of a word in the main memory is called its address.

- Width of the data bus: memory is read and written to/from registers in the processor and locations in main memory. Each such operation is performed on a single word at a time. The size of the word is determined by the number of physical connections (lines) between the processor and the memory system.

This survey of memory technology presents excellent review of the hardware methods used by different memory technologies, and how they impact on the way programmers use memory. (This paper is based on Linux perspective; it is about 100 pages.)

Hardware Perspective

At the lowest level, the processor views the main memory in a very simple manner; a fast storage medium. The main memory is used to store all the data a process needs for its computation (e.g., parameters, variables, objects, etc.). To perform any operation on a piece of data (word-sized), the following cycle must be followed:

- Load the data from memory into internal processor registers.

- Apply the operation on the registers and put the result in another register.

- Optionally, write the result from the register into the relevant memory location.

The primitive operations that the processor uses with relation to memory are:

Read (Address), (Register): copy the content of the word stored at (Address) into the (Register) of the processor. Registers are referenced by their number (0, 1, … number of registers on the processor).Write (Register), (Address): copy the content of the (Register) to the memory cell at (Address).

For example, consider the following Java code:

int i = 10;

int j = 20;

i = i + j;

The compiler generates the relevant code for the CPU to execute. The generated code in an abstract set of processor instructions would look like the following code; by convention, we write [var] to denote the address in memory in which a variable is stored.

;; Initialize the memory cells for i and j

WRITE $10, [i] ;; 10 is a constant value

WRITE $20, [j] ;; 20 is a constant value

;; Execute the sum

READ [i], R1 ;; copy the content of i in register 1 (R1)

READ [j], R2 ;; copy the content of j in register 2 (R2)

ADD R1, R2, R3 ;; execute the operation: R1 + R2 and store the result in R3

WRITE R3,[i] ;; store the result in the memory location of i

Programming Language Perspective

We start with a discussion of how Java constructs relate to memory. We then compare the Java approach with the C++ approach and stress the differences.

Which explicit/implicit memory-related services we already used in Java?

- Explicit

- Object allocation - Object allocation using

new - Initialization - Constructor invocation or variable initialization

- Copying - Copying data from one variable to another

- Object allocation - Object allocation using

- Implicit

- Object deletion - done by the Garbage Collector

- Variable allocation - Local (primitive) variables allocation

- Variable deallocation - Local variable deallocation when leaving scope

Memory Access

In high level languages, there is usually only one way to access memory: through a variable. A variable in Java is characterized by:

- A name

- A type

- A scope: the program region in which the name is recognized and refers to the same variable

Variables are bound to values at runtime. A value is characterized by:

- A type

- A position in memory which is the value address

- A size - how much memory does the value requires in memory

When a variable is bound to a value, the type of the value must be compatible with the type of the variable. Types are compatible when:

- They are identical

- The type of the value is more specific in the inheritance hierarchy than the type of the variable.

- The type of the value implements the type of the variable (when the type of the variable is an interface).

Stack model vs. Heap model

Modern programming languages employ two different memory models, to satisfy different needs, namely the Stack (a.k.a. the call-stack) and the Heap. Before diving into the design and usage of these models we first need to understand how calling procedures/functions/methods effects the memory model.

Procedures

High level languages usually employ the concept of procedures (or functions, methods, routines, etc). A program is composed of several procedures. Each procedure is a small piece of code, which can receive arguments, define variables, perform a simple and defined operation and optionally return a value. Procedures may call other procedures or themselves. Note that even object oriented programs are, under the hood, procedural. When you call a member method of some object, you basically call the method with the object as one of the arguments. Indeed, in some languages (e.g., python, perl, etc.), you are required to pass the object as the first argument!.

The Call Stack

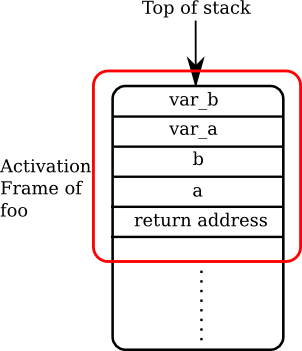

Procedural calls can be viewed in a stack-like manner; each procedure’s activation (a.k.a., function call) requires a dedicated frame on a stack. This function-call-dedicated stack frame is called an Activation Frame. Each time a procedure is called, a new activation frame is generated on the stack1. Each activation frame holds the following information:

- The parameters passed to the procedure

- Local primitive variables declared in the procedure

- The return address - Where to return to when the procedure ends

For example, consi der the following code:

public static void foo(int a, bool b){

int var_a;

int var_b;

.

.

.

}

Each time the function is invoked, an appropriate activation frame will open on the stack, which will look something like this:

When an activation frame is created, the binding between local variables and their location on the stack is made. When a procedure terminates, its associated activation frame is popped from the stack, and (figuratively) discarded.

In Java, only the variables located on the top-most activation frame may be accessed (parameters and local variables)2. However, as we will see, this is not the case in C++ (and we are not referring to pointers!).

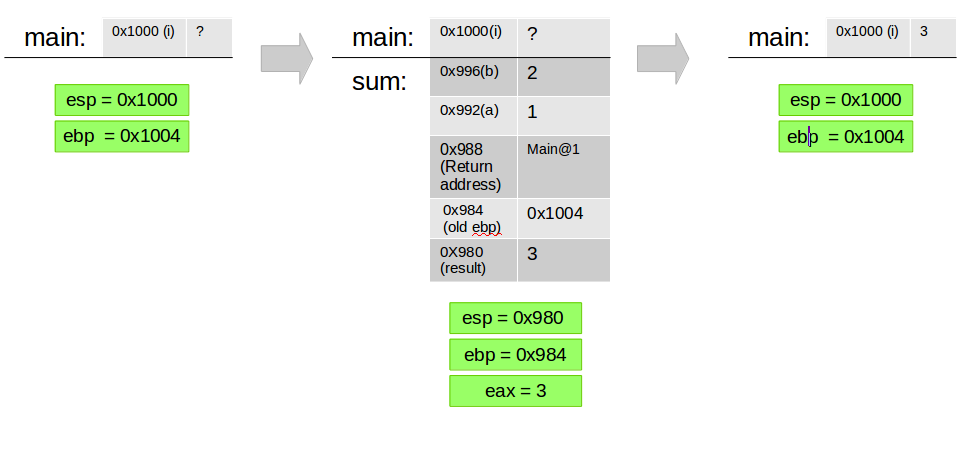

Stack Implementation

To realize the concept of procedures and activation frames, modern computer systems inherently support the call stack data structure; For each execution element (process, thread, etc.) there exists an associated memory region which is called the call stack. The operating system is responsible for allocating enough space for the stack of each process (or thread), and the process (or thread) implicitly, using a code generated by the compiler, manages the stack on its own. The stack is defined by two CPU registers: esp, the stack pointer, which points to the top of the stack (initialized by the operating system) and ebp, the base pointer, which points to the start of the current stack frame - immediately before the first local variable. These registers may be directly modified by the process (or thread), by assigning different values, or indirectly modified, by pushing and popping words to/from the stack and calling or returning from a function. Remember, esp always point to last taken address in the stack while ebp points to the first address in the stack frame - immediately before the first local variable, this address will also contain a backup of the previous ebp.

Depending on the machine you are using, the way that the stack is manipulated in order to perform method invocation is called the “Calling convention”. Mainly, a calling convention is an implementation-level (low-level) scheme for how functions receive parameters from their caller and how they return a result.

In C calling convention (also known as cdecl) parameters are loaded to the stack from right to left by the caller and the return value is commonly stored in the eax register (although on some cases ecx and edx are also used). Finally, the caller is also responsible for removing the pushed parameters from the stack after the invoked function returns.

For example, Observe the following code:

int sum(int a, int b);{

int result = a + b;

return result;

}

void main() {

int i = sum(1,2);

}

The main method will get translated = compiled to a code equivalent to:

push 2//will write the constant “2” into the top of the stack and subtract 4 from esppush 1//will write the constant “1” into the top of the stack and subtract 4 from espcall sum//push the return address to the stack (subtracts 4 from esp)mov [ebp - 4], eax//read the value in eax and store it in the memory location for iadd esp, 8// performs esp = esp + 8; cleans the memory that holds “2” and “1”

While the sum method will get translated to:

push ebp// backup the old ebp (subtracts 4 from esp)mov ebp, esp//set the current ebp to point to the current esp location which is directly after the return addressmov eax, [ebp+8]//read the value stored in the address that contained before the returned address (the a parameter) into eaxmov ebx, [ebp+12]//read the value stored in the address that contained 4 bytes before the returned address (the b parameter) into ebxadd ebx, eax// add the values stored in eax and ebx and store the result into ebxpush ebx//push the result into the stack (subtracts 4 from esp)mov eax, [ebp-4]// set the return value in eaxmov esp, ebp// set esp to clean all the local variables of sum.pop ebp// restore the old ebp from the stack (adds 4 to esp)return// return back to the caller, pops the return address from the stack (adds 4 to esp)

One important issue to notice is that the compiler has to know the offset in the stack in which a local variable is stored in compile time, in addition it must know the size of the stack frame in order to rewind it when returning - this means that each variable in the stack must be of a constant size and each method-stack-frame is also of a constant size.

Stack: Advantages and Disadvantages

This implementation of the call-stack memory model provides a fast managed memory - the memory used by the stack is automatically discarded when popping the stack frame just by changing the value of a single register. In addition, the compiler is responsible of generating the instructions that manipulate the stack and therefore can optimize them. On the other hand the stack is often limited in size and in addition one cannot use values that resides inside a stack frame once it is popped (i.e., by one of the methods that correspond to the upper stack frames). Another limitation is that since the compiler generate the instructions that manipulate the stack at compile time - the allocations must be static and the size allocated must be known at compile time.

Heap

Sometimes, programs need to store information which is relevant across function calls, too big to fit on the stack, or of size that is unknown at compile time. We would like to be able to specify that we want a block of memory of a given size to store some information. We usually do not care where the memory comes from, we are just interested in getting a block of it for our use. As a result, we abstract this service as a heap, where blocks of memory are heaped in a pile, and we can get to the block we need if we remember where we left it.

Before we go into the details of how usually heaps are implemented by an RTE, let us see where we have made use of the heap in Java. In Java, there is a clear distinction between what is saved on the stack and what is stored on the heap. In Java, all local variables of methods are stored on the stack and all Objects, are stored on the heap.

Consider the following code snippet:

int i = 5;

Object o = new Object();

Here, both i and o are stored on the stack. Only the new Object allocated by new is stored on the heap. The section of the stack represented by the variable i contains the binary representation of 5 (00...00101). So, what is stored in o’s section?

We need to make a clear distinction between the Object which might be very big, with enough space to hold the entire state of Object, and the variable o which holds the location of the Object on the heap! More specifically, the section associated with o on the stack holds a reference (a number) to the starting location of the block of memory new allocated to hold the instance of the new Object().

This distinction between Objects and primitives in Java explains why primitives are always passed to functions by value and Objects always by reference.

Heap Implementation

The heap is implemented with the collaboration of the Operating system and the RTE (even programs executing directly beneath – or above, if you prefer – the operating system usually employ a wrapper around the coarse control the operating system provides, which in turn defines the RTE).

More on man: man man.

The OS (physically) allocates a large block of memory to each process, as the process starts, to serve as its heap. This block is shared by all the threads in the same process, and may be enlarged during the life time of the process by using special system calls (e.g., brk(2)3). Smaller blocks are then (logically) allocated to hold specific data items (e.g., Objects). Allocating smaller blocks from the heap, keeping track of which parts of the heap are used at any given time, and requesting the OS to enlarge the heap are the responsibility of the RTE and are usually done transparently.

Note that managing the heap is done by the RTE while managing the stack is done with code instructions inserted by the compiler.

Memory Deallocation in Java

As we have already mentioned, blocks of memory are allocated in Java only when creating new Objects. Each time we call the new operator, a block of memory is allocated, large enough to hold the Object we are instantiating.

However, we have not mentioned how memory in Java is freed. What happens to an Object once we have no further use for it? e.g., we allocated an array inside some function, and then left the function without leaking the reference to the array outside of the scope of the function. Should the array be kept in memory indefinitely? No. This would exhaust our memory rapidly. We would like to reuse the memory used by the array, in a way to tell the RTE that the memory can be recycled. In Java, this is done automatically for us, by an active entity which is called the garbage collector.

The JVM Garbage Collection Process

Automatic garbage collection is the process of looking at heap memory, identifying which objects are in use and which are not, and deleting the unused objects. An in-use object, or a referenced object, means that some part of your program still maintains a pointer to that object. An unused object, or unreferenced object, is no longer referenced by any part of your program. So the memory used by an unreferenced object can be reclaimed.

In a programming language like C, allocating and deallocating memory is a manual process. In Java, process of deallocating memory is handled automatically by the garbage collector. The basic process can be described as follows.

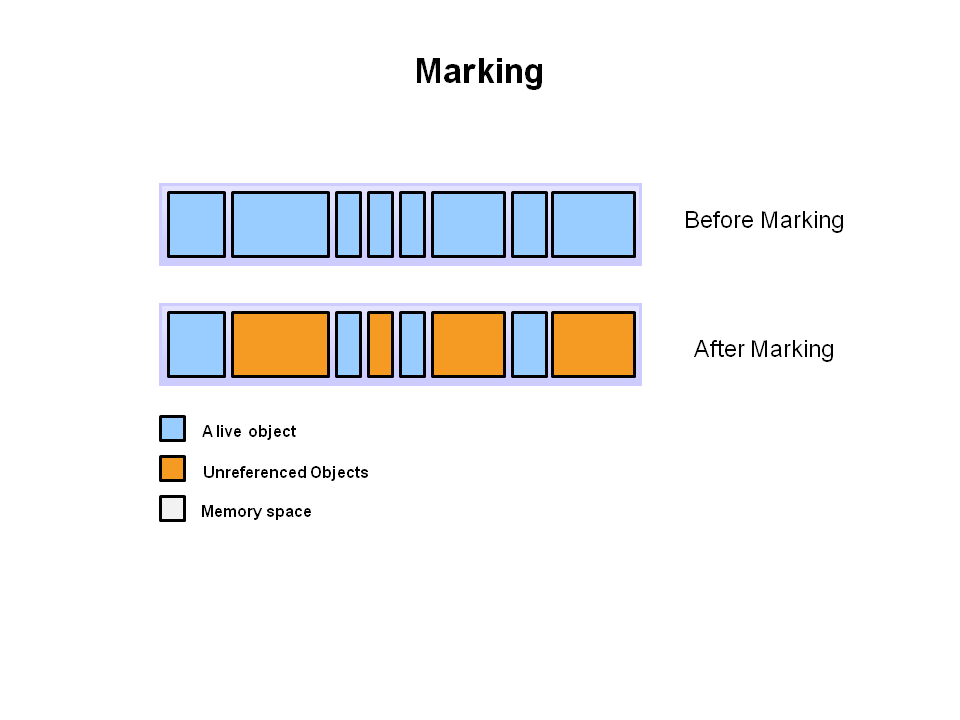

-

Marking: The first step in the process is called marking. This is where the garbage collector identifies which pieces of memory are in use and which are not. This process can be done by: a. Composing a set of all Objects referenced from the stack and from registers. b. For each Object in the set, adding all Objects it references. c. Repeat step (b) until the set remains unchanged (in essence, compute the transitive closure of the “a references b” relation).

-

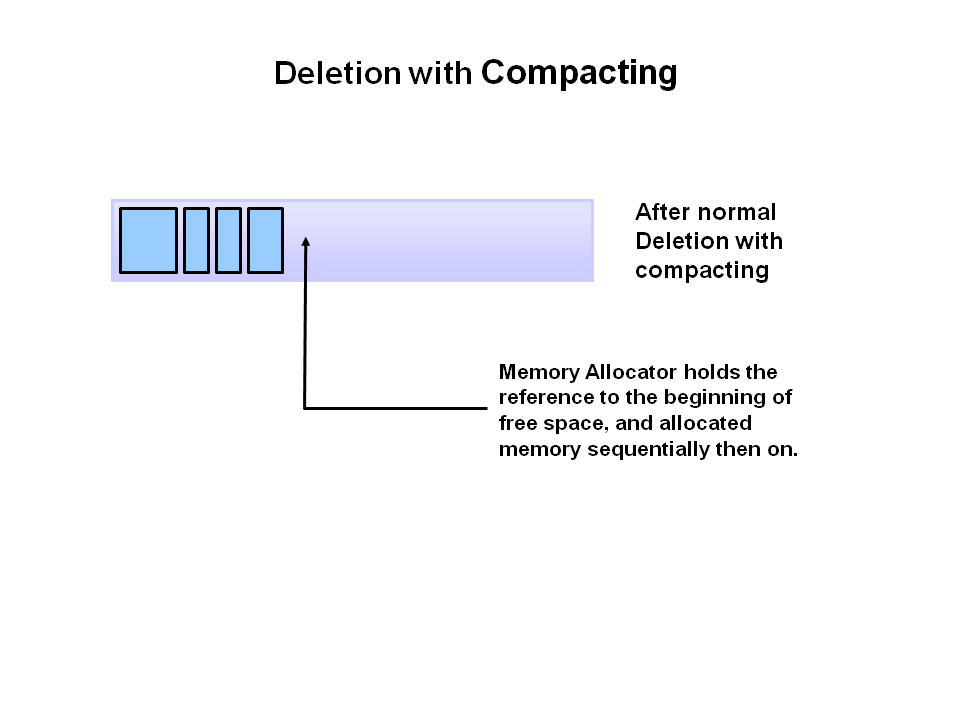

Deletion with Compacting: Removes unreferenced objects leaving referenced objects and pointers to free space, to further improve performance, in addition to deleting unreferenced objects, the garbage collector also compact the remaining referenced objects. By moving referenced object together, this makes new memory allocation much easier and faster.

Of course this process may have many ways to implement, given some program behavior some will perform better then others and therefore, depending on your program needs you can choose which garbage collection algorithm to use when starting your java application.

While a java program is executed, once in a while, the garbage collector kicks into action and recycles, or frees, garbage Objects. You can read more about the JVM’s Garbage collection process here. In addition, this article presents an excellent survey of these techniques: Practical Garbage Collection, part 1 - Introduction (Peter Schuller, December 2011).

Heap: Advantages and Disadvantages

The Heap model allows for dynamic memory allocation - i.e., the size of the allocation does not have to be known at compile time. In addition memory on the heap stays on the heap until it is explicitly freed (either by the user or by the garbage collector), finally the heap is much larger than the stack and consists from most of the memory available to the process (the virtual memory). On the other hand - heap allocation costs more than stack allocation (as the runtime must find an empty memory location to allocate on the fly) and can cause memory fragmentation. If the user is responsible to free the allocated memory by hand - the program may be pruned to memory leaks and access to non-allocated memory. If the runtime is responsible to free the allocated memory (i.e., using automatic garbage collection) - the performance of the program may degrade as CPU time will be dedicated for the garbage collection execution and also since most garbage collection algorithms require to stop all or some parts of the program while they perform the cleaning.

Manipulating the Stack and the Heap in C++

While the general abstractions of stack and heap are similar in C++ and Java, there are fundamental differences in how they are managed. Generally speaking, C++ allows the programmer more control over memory than Java. However, such a level of control comes with a price (or lines of code to write if you wish), and requires the programmer to completely understands the environment in which her program will execute in order to avoid (the very large) pitfalls.

Stack

The stack in C++ is managed in the same way the stack in Java is managed, with one important difference: objects in C++ may be allocated on the stack. This means that they can be passed by value to functions! Moreover, when an activation frame is deleted, objects are not just discarded as primitive types are, but before destroying them the C++ RTE ensures that a special function of the object will be called, namely, the destructor. A destructor is a function written by the programmer which is in charge of cleaning after the object: releasing the object state, and any resources the object might have acquired.

We later discuss three important methods of objects in C++: The destructor, copy constructor and assignment operator.

Stack allocation in C++

Depending on your perspective, syntax choices for object allocation and initialization in C++ embody either an embarrassment of riches or a confusing mess. The following are examples of stack allocations and initializations:

int x(0); // initializer is in parentheses

int y = 0; // initializer follows "="

ObjectType o(10); // call ObjectType's ctor with argument 10

ObjectType o2; // call ObjectType's default constructor

The following are examples of syntax that seem like a regular stack allocation but does not do what you expect

// In modern C++, it behaves just like `ObjectType o3(10);`

// but some old C++ compilers created a new ObjectType on the stack by calling ObjectType's ctor

// with argument 10 then call the copy constructor to copy the new object into o3

ObjectType o3 = ObjectType(10);

// this will NOT call the default constructor!

// but instead declare a function named o4 that accept no arguments and return ObjectType

// (to understand why you can read about C++'s most vexing parse rule.)

ObjectType o4();

This syntax proved to be extremely confusing and the source of huge amount of errors, therefore, newer versions of C++ introduce the bracket initialization syntax:

int z{ 0 }; // initializer is in braces

ObjectType o2{10}; // call ObjectType's ctor with argument 10

ObjectType o2{}; // call ObjectType's default constructor

Objects on the stack and pass by value Consider this example:

class Counter {

public:

int i;

Counter() : i(0) {cout << "default constructor" << endl;}; //default constructor

Counter(const Counter &other) : i(other.i) { cout << "copy constructor" << endl; }; //copy constructor

~Counter() {cout << "destructor" << endl;} //destructor

void inc() {

this->i++;

}

};

Counter increment(Counter counter2) {

counter2.inc();

return counter2;

}

int main(){

Counter counter1;

Counter counter3 = increment(counter1);

cout << "counter1: " << counter1.i << ", counter3: " << counter3.i << endl;

return 0;

}

At runtime, the following takes place:

- A place to hold class

Counteris reserved on the stack and is bound with the variablecounter1. - A place to hold class Counter is reserved on the stack and is bound with the variable

counter3. - The default constructor is called for

counter1 - An activation frame for

incrementis created, with enough space to hold the return address and an object of classCounter. - A new object of class Counter is instantiated on the stack, by using the copy constructor of class

Counterand passingcounter1as the argument. - The method

inc()of the objectcounter2vis called. counter2is copied by the copy constructor of class Counter to the location ofcounter3.- The destructor of

counter2is called. - The increment frame is popped from the stack and the program continues from the return address.

Note that: 1. Changes made on counter2 are not reflected in counter1; 2. increment implicitly created 2 additional Counter objects, instantiating, copying and destructing them!

Therefore, the resulted output of the program will be:

default constructor

copy-constructor

copy-constructor

destructor

counter1: 0, counter3: 1

destructor

destructor

Heap

As everything in C++ can be allocated on the stack, so can everything be allocated on the heap. Even primitive types. For example, we can allocate an int or an object of class Foo on the stack:

int *i = new int(8);

Foo *foo = new Foo(42);

*foo is a pointer, we will learn more about these on the next lecture - but for now just think about those as a number that can be serve as an index to a huge array of bytes - our main memory.

New and Delete Operators

Allocating on the heap is achieved by calling the new operator. Note, new is an operator, not a function (which we will explain in the following lectures), which allocates space on the heap and initializes the space as we requested by calling a constructor.

Please notice that the returned value of new a_type(vars) is always of type a_type*, which is called a pointer to a_type (but more on pointers in the next lecture).

The memory is initialized using the constructor we requested (which must exists, otherwise our code will not compile).

In contrast to Java, memory allocated on the heap in C++ is never garbage collected, and it is the responsibility of the programmer to free the memory. For example, to free the memory we allocated earlier we will use the following code:

delete i;

delete foo;

Each time we delete an object, its destructor is called.

-

Who actually creates the activation frames? Well, the procedure itself. The compiler generates the appropriate code, and inserts it as the preamble of each procedure. ↩

-

Variables’ binding is usually very simple, as access to variables must be really fast. The compiler hard-codes the location of each variable in the procedure’s code, usually using a simple offset from the start of the activation frame. ↩

-

Man is a shorthand for Manual (as in a guide, reference). The man is the standard documentation system on any unix system, which contains the documentation (help files) for all the standard utilities (try running

man commandwherecommandis any shell command you have previously used), system calls and libraries installed on the system. The man is arranged in section, numbered consecutively, where section 1 is for utilities, section 2 for system calls, section 3 for library calls etc. The convention when mentioning a utility/system call/library call is to mention within brackets in which section of the man it resides. For example,brk(2)tells us thatbrkis a system call. Look it up usingman 2 brk. ↩