bguspl

In this lecture, we introduce the notion of concurrent computation and learn about the threading facilities of Java.

Processes and Scheduling

Process vs. Program

In a previous lecture, we defined processes as the basic unit of execution managed by Operating Systems. An Operating System, as any RTE, executes processes. The Operating System creates processes from programs, and manages their resources.

Let us elaborate what is meant by a process resource. To keep running, a process requires at least the following resources:

- The program (from which the process is created)

- Three blocks of memory: the stack, the heap and the code

- Tables for resources of specific types: File handles, socket handles, IO handles, window handles.

- Processor state information: contents of registers1, Program Counter (PC), Stack Pointer

The program context is defined as the Program Counter, the Registers and all the memory associated with the process. Practically, the program context contains all the information the OS needs to keep track of the state of a process during its execution.

Scheduling

Operating Systems have the capability to run more than one process ‘simultaneously’ on a single computer. In most cases, an OS runs more processes than there are physical processors in hardware. The OS is, therefore, responsible to interleave the execution of the active processes – that is, the OS runs a process a little while, interrupts it and keeps track of its context in memory, then runs another process for a little while, and it keeps switching this way from process to process. The component of the OS responsible for sharing the CPU between processes is called the scheduler. To control the scheduling activities, the scheduler maintains a list of all active processes in the system, and at some point decides to switch from one executing process to another.

Scheduling Paradigms: There are two paradigms with which the scheduler may interact with the currently active processes:

- Non-Preemptive Scheduling - An executed process run until it decide to pass control back to the scheduler so it will be able to choose another process to continue its execution

- Preemptive Scheduling - A running process is interrupted in a timely manner and the control is passed back to the scheduler so it will be able to choose another process to run

Context Switch

A context switch is the operation that occurs when the OS switches between one executing process and the next one the scheduler chose, and may consume several milliseconds of processing time (that is, a context switch can take the long time relative to simple CPU operations). The context switch is transparent to all processes, meaning a process is not able to tell it was preempted. A context switch in a preemptive system (most operating systems) includes at least the following sub-steps:

- Timer interrupt - suspend the currently executing process (the old process) and start the execution of the scheduler

- Save the context of the process, so that it may be resumed later

- Select the next process to execute (use a scheduling policy)

- Retrieve the context of the next process to execute

- Restore the state of the new process: restore the registers and the program counter.

- Flush the CPU cache (as the new process has a new memory map, it can not use the cache which is filled with the data of the old process)

- Resume the new process (start executing the code of the new process from the instruction that was interrupted)

The most costly operation (amortized over the lifetime of a process) is flushing the CPU cache. One of the most expensive operation when executing a process, is accessing the memory. The reason is that accessing a cell of memory in RAM is much slower than executing a computation step on the CPU. To reduce this cost, the CPU maintains a cache of frequently used memory cells in a small very-fast memory section, located on the CPU. When a memory cell is copied in the CPU cache, it can be read and written as fast as executing a single computation step on the CPU. When there is a context switch, all the memory cells stored in the CPU cache become invalid - since they refer to values from the old process. Therefore, the whole cache must be ``flushed’’ (that is, all the cells must be written back to actual RAM and cleared).

Actually, the CPU cache is not flushed, only a part of it which is called the TLB. We will not discuss the TLB during this course, as you will discuss it next year in the Operating System course. More info for interested parties can be found here.

Can we reduce the cost of context switch?

Threads2

Let us start by trying to design a video player, which should be able to play a compressed video stream.

The video player example

The player should take the following steps in playing the video:

- Reading the video from disk

- decompressing the video

- decode the video and display on the screen

Now, if the video is very small, say a few Megabytes, we have no problem. We can read the entire video into memory, decompress it and then display it on the screen. However, consider what will happen when the video is larger than the actual memory your computer has? and what if the video is downloaded from the Internet, and you want to start watching it before the download completes (e.g., YouTube)?

The Interleaving solution

Consider the following solution: read some of the video data (from disk or the network), decompress it, decode it and display on the screen. Repeat until the video ends. Let us call this the “Interleaving” solution. Lets look at an example java code for the interleaving solution:

public Class VideoPlayer {

private Screen screen; //an assumed class representing the screen

private ByteBuffer bytes;

private FrameBuffer frames; //an assumed class representing buffer of frames

public VideoPlayer(Screen screen) {

this.screen = screen;

this.bytes = ByteBuffer.allocate(1<<10); // buffer of 1K bytes

this.frames = new FrameBuffer();

}

public void play(File videoPath) throws Exception {

FileChannel videoChannel = new FileInputStream(videoPath).getChannel();

while (videoChannel.read(bytes) >= 0) { //this line requires waiting to the relatively slow disk

frames.decode(bytes); //perform the actual decoding of the video

//the following lines of code requires waiting until the screen finish showing the decoded frames

//In addition, we want the screen to display maximum of 25 frames per second

//so that the video will play on the right rate.

while (!frames.isEmpty()) {

screen.show(frames.next());

screen.wait(1000/25); //in order to achieve 25 frames per second

}

}

}

}

There is one problem that we might find when running the interleaving solution - the video playback will not be smooth - and will occasionally freeze, these happens because when we reading from disk or decoding the frames, we cannot show new video frames.

The multi-process solution

So, why not try a different approach? Since the task of playing the movie is easily decomposed into several independent tasks, why not have one process read the movie, the next one to decode it and the final one which displays the movie on the screen. This solution will allow reading the bytes while decoding the frames and decoding the frames while showing the previous ones on screen which will allow for a much smoother experience!

This seems like a great idea, However, another difficulty arises; how will all of these processes communicate with each other? That is, how do we send information from one process to the next? (We will learn how to transmit information across processes in Chapter 3 – but we can already tell that it introduces a high cost in terms of performance and requires a fair amount of coding, debugging and maintaining.)

The multi-threading solution

If we could have only one process, which would be able to do all of these task simultaneously, our life would be much more tolerable.

To our rescue comes the concept of Threads. In a single process, several threads may be executing concurrently. They share all the resources allocated to the process, and may communicate with each other using constructs which are built in most modern languages, thus making the programmer happier. In contrast to different processes, threads inside the same process share the same memory space (however, each thread has its own stack), the same opened files and access rights. Moreover, the cost of a context switch between threads in the same process is much lower than between processes or threads of different processes, as the CPU cache need not be flushed3.

To conclude our example problem of the video player, we can now design a single process with several threads. One thread will read the video channel and place chunks of it in the chunk queue. In parallel, another thread will read the video data chunks from the chunk queue, decode them into frames and place them into the frames queue, the final thread takes frame after frame from the frame queue and displays them on screen. Voila.

Applications of Concurrency

-

Advantages Concurrency opens up design possibilities that would be impractical otherwise. Threads liberate you from the basic limitation of invoking a method and blocking, doing nothing, while waiting for reply. There are many reasons for using threads, the most prominent are listed here:

-

Reactive Programing: Some programs are required to do more than one thing at a time, performing each as a reactive response to some input. Our example of the video player falls here. Another large group of programs falls in this category: GUI applications. It seems impossible to program a GUI without concurrent programming.

-

Availability: One of the most common design patterns for programs that are service providers (we will review it thoroughly when discussing networking) is to have one thread as a gateway for incoming service consumers and a different thread for handling the requests of each one. For example, an FTP server will have a gateway thread to handle new clients connecting and a separate thread (per client) to deal with long file transfers.

-

Controllability: A thread can be suspended, resumed or stopped by another thread. This gives the designer and programmer a freedom that he would not be able to gain otherwise.

-

Simplified design: Software objects usually model real objects. In real life objects in many cases are acting independently and in parallel. Even if not modeling real objects, designing autonomous behavior is in many cases easier than designing sequential (interleaving between objects) one. For example recall the video player discussion.

-

Simplified implementation: With threads it is simple to implement cases where a process needs to wait for external blocking event but perform some other vital processing in the meanwhile.

- Parallelization: On multiprocessor machines, the operating system can execute threads truly concurrently with one another by allowing one thread to run on each CPU. Even if only one CPU exists, interleaving the execution paths avoid delays when it comes to part of the program that is busy doing some heavy computation or waiting for events.

- Even if you choose not to use threads some services provided by modern RTE operate in a concurrent manner, hence leaving you no choice rather than mastering concurrent programing.

-

-

Limitations Benefits of concurrency should be weighed against its cost in resource consumption, efficiency and program complexity:

- Safety: when multiple threads share resources (this is the most common case) they need to use some synchronizations mechanisms to ensure that they maintain consistent state (we will elaborate on that in the next lecture). Failing to do so may lead to random looking, hard to debug inconsistencies.

- Liveness: In concurrent programming a thread may fail to be alive - an activity performed by a thread may stop for many reasons we will explore later.

- Non determinism: No two executions of a concurrent program need be identical. This makes multi-threaded program harder to understand, predict and debug.

- Context switching overhead: when a job performed in a thread is small enough the overhead of thread creation and context switching overrides the benefits.

- Request/Reply programing: Threads are not a good choice when an object actually needs to wait for a reply from another object in order to continue. In such cases synchronizing the activities costs extra time and introduce more complexity.

- Synchronization overhead: even with good design where multi-threading is necessary , synchronization can not be avoided. Synchronization constructs consume execution time and add complexity.

- In some (rare) cases where activity is self contained and sufficiently heavy it may be easier to encapsulate it in a different standalone program. A standalone program can still be accessed via system level services.

Threading Support in Java

Java (in fact, the JVM) has a first class support for threads. Until now, you have been using only sequential execution; consider the following class, MessagePrinter, which has a simple method run(). When this method is invoked, the object prints a message which it received in its constructor.

/* this class abstracts a an objects which receives a message and prints it.

The Runnable interface requires a single void method, run() - which also makes it a functional interface (i.e., a candidate for lambda)*/

class MessagePrinter implements Runnable {

protected String msg;

protected PrintStream out; // The place to print

MessagePrinter(PrintStream out,String msg) {

this.out = out;

this.msg = msg;

}

/* print the message */

public void run() {

out.println(msg); // display the message

}

}

You can use this class in the following fashion:

class SequentialPrinter {

public static void main(String[] args) {

MessagePrinter helloPrinter = new MessagePrinter(System.out, "Hello");

MessagePrinter goodbyePrinter = new MessagePrinter(System.out, "Goodbye");

helloPrinter.run();

goodbyePrinter.run();

}

}

In this example, the JVM first loads the SequentialPrinter class and calls the main() function. The JVM now execute the code inside the SequentialPrinter class. Next, two new objects are created - helloPrinter and goodbayPrinter. Next, helloPrinter::run method is called. Last, goodbyePrinter::run method is called also.

The result is two words printed to the screen, one after the other. First, “Hello” is printed, then, “Goodbye”.

Lets now consider a Multithreaded version, using a different thread for each of our MessagePrinters:

class ConcurrentPrinter {

public static void main(String[] args) {

MessagePrinter helloPrinter = new MessagePrinter(System.out, "Hello\n");

MessagePrinter goodbyePrinter = new MessagePrinter(System.out, "Goodbye\n");

Thread helloThread = new Thread(helloPrinter);

Thread goodbyeThread = new Thread(goodbyePrinter);

helloThread.start();

goodbyeThread.start();

}

}

In this example, the JVM first loads the ConcurrentPrinter class and calls the main() function. The JVM now impersonates the class ConcurrentPrinter. Next, two new objects are created, both of the MessagePrinter class. Next, two new special objects - threads are instantiated. Each thread receives as an argument a Runnable object. Calling Thread::start starts a new ‘thread of execution’ (hence the name) which has as an entry point the run function of its given runnable.

Now, since we have two separate threads, each invoking the run() method of a different MessagePrinter object (and possibly at different times), we cannot know ahead of time which message will be printed first.

The Thread API

Every piece of code that is executed in java is executed by some thread, you can allways receive the thread that is executing the current code using the static method Thread.currentThread().

Java threads has some several important methods - we already saw two of them:

-

A constructor which receives a runnable - this will set the run method of this runnable as the entry point of the thread.

-

A start method which starts the thread of execution - first it will allocate a stack for this thread and then start it on its entry point.

Lets examine other important methods.

Thread Joining

When ever a thread wants to wait to another thread to complete it can use the join method of that thread:

public static void main(String[] args) {

System.out.println("Threads are legend... ");

Thread barney = new Thread(() -> {

for (int i=0; i<100; i++) {

System.out.println("wait for it...");

}

});

barney.start();

barney.join();

System.out.println("ary!");

}

Thread Interruption

Consider the following simple code, which does almost nothing, does it bad, and, in addition, never ends:

public static void main(String [] args) {

Thread stopper = new Thread(() -> {

long time = System.currentTimeMillis();

while (true) Thread.yield();

System.out.println("run for: " + (System.currentTimeMillis() - time) + " millis");

});

stopper.start();

doSomethingThatTakesTime();

//how can I stop the stopper now so it will print the time???

}

When executing the code above, (at least) two threads are created: the first thread is the main thread, which starts executing the main function. The second thread is stopper. Now after the main thread finish with its task it wants to somehow stop the stopper - but how?

The first option you might think about is somehow killing (a.k.a., stopping) the stopper thread - but that means that the stopper thread will just die while on the while loop without giving it the chance to print the time. In fact, killing threads is almost always a bad choice as the threads may leave the state of the program in an unpredictable and illegal state. This is why although java threads has a close method, it is deprecated.

Another option that seems much more reasonable is to have the thread constantly check for a stop condition and exit the loop once it met:

public static void main(String [] args) {

AtomicBoolean stop = new AtomicBoolean(false); //a wrapper to a boolean that is sutable to

//be written to and read from different threads

//we will learn more about those classes on later

//lecture.

Thread stopper = new Thread(() -> {

long time = System.currentTimeMillis();

while (!stop.get()) Thread.yield();

System.out.println("run for: " + (System.currentTimeMillis() - time) + " millis");

});

stopper.start();

doSomethingThatTakesTime();

stop.set(true);

stopper.join();

}

While this option solves the problem we had in the previous one it still has some problems. Lets for example revisit our stopper code, it seems very inefficient to have the stopper constantly spin inside the while loop, we can improve this code a little by sleeping for a while before rerunning the loop. (Note though that like the previous solution - this too far from perfect):

public static void main(String [] args) {

AtomicBoolean stop = new AtomicBoolean(false);

Thread stopper = new Thread(() -> {

long time = System.currentTimeMillis();

while (!stop.get()) {

sleep10Seconds(); //assume that we have this function for now..

}

System.out.println("run for: " + (System.currentTimeMillis() - time) + " millis");

});

stopper.start();

doSomethingThatTakesTime();

stop.set(true);

stopper.join();

}

The problem here is that if we change the stop variable to true it may take 10 seconds before the stopper thread will react - therefore it will both print the wrong time and also make the main thread wait for no reason.

To our help comes the Thread interrupt flag.

An interrupt is an indication to a thread that it should stop what it is doing and do something else. It’s up to the programmer to decide exactly how a thread responds to an interrupt, but it is very common for the thread to terminate. A thread sends an interrupt to another thread by invoking the interrupt method of that thread. For the interrupt mechanism to work correctly, the interrupted thread must support its own interruption.

Lets go back to the previous case, where the stopper constantly checks for the stop condition and change it to use interrupts:

public static void main(String [] args) {

Thread stopper = new Thread(() -> {

long time = System.currentTimeMillis();

while (!Thread.currentThread().isInterrupted()) {

Thread.yield();

}

System.out.println("run for: " + (System.currentTimeMillis() - time) + " millis");

});

stopper.start();

doSomethingThatTakesTime();

stopper.interrupt();

stopper.join();

}

Using interrupts we remove the need for the stop variable, but what about the later case (with the sleep)?

In java, many of the method that blocks a thread execution (like sleep) throws an interrupted exception, this exception is thrown by the method if the thread was interrupted while it is blocked, therefore we can solve the “sleep” problem as follows:

public static void main(String [] args) {

Thread stopper = new Thread(() -> {

long time = System.currentTimeMillis();

try {

while (!Thread.currentThread().isInterrupted()) {

Thread.sleep(1000 * 10); //10 seconds

}

} catch (InterruptedException ex) {

//this will get thrown by the Thread.sleep method in the case of interrupt

//and will force us to leave the loop

}

System.out.println("run for: " + (System.currentTimeMillis() - time) + " millis");

});

stopper.start();

doSomethingThatTakesTime();

stopper.interrupt();

stopper.join();

}

you can read more about the interrupt flag here.

When to use threads?

If using threads allows us to use more CPUs then we should always use threads right? NO!

The first reason is that using threads complicates our code. if we don’t really need the performance improvement, converting our code into multi-threaded is just not worth it: REMEMBER! PREMATURE OPTIMIZATION IS THE ROOT OF ALL EVIL!!!

The second reason is that on some occasions using threads will actually make our program slower! In order to demonstrate this phenomena lets say that we received a job to write a function that gets a matrix nXm and creates a vector of length n which has in each cell i the sum of the elements in the the ith row of the matrix.

A sequential version for this function can be:

double[] seqRowSum(double[][] matrix) {

double[] vector = new double[matrix.length];

for (int i=0; i<matrix.length; i++) {

for (double v : matrix[i]) {

vector[i] += v;

}

}

return vector;

}

This version is fairly straight forward to follow, debug and maintain. One option for a parallel version of this function is to create a thread for each row and make it calculate the sum of this row, this way we hope to have all the rows calculated in parallel:

static double[] paraRowSum(double[][] matrix) throws InterruptedException {

double[] vector = new double[matrix.length];

Thread[] threads = new Thread[matrix.length]; //thread for each row

for (int i = 0; i < matrix.length; i++) {

int fi = i; //an effectively final copy of i

threads[i] = new Thread(() -> {

for (double v : matrix[fi]) {

vector[fi] += v;

}

});

threads[i].start();

}

for (Thread t : threads) {

t.join();

}

return vector;

}

This version looks much more complicated, it has more code, and it is much harder to debug - the only question is - is it worth it?

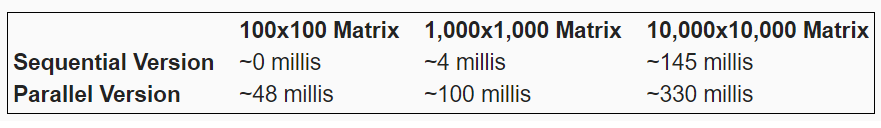

Tested on a Intel(R) Core(TM) i7-6700HQ CPU @ 2.60GHz with 16G of RAM machine, we received the following results:

Why did we received such a bad results for the parallel execution? The first thing that we need to understand is that threads creation takes both time and memory. For each thread that you create you must first allocate a stack and then request the operating system to start a new thread using that stack - this overhead is significant as in our case we creating as many threads as there are rows in the matrix.

The second thing to understand is that many threads means many context switches - and while switching context between threads of the same program has less overhead than process context switch - the overhead still exists!

Therefore, the first thing that we want to do in order to improve the performance of our parallel version is to allocate less threads. In order to do so we will use the idea of thread pools.

A thread pool manages a pool of worker threads, it contains a queue that keeps tasks waiting to get executed. the workers monitors the internal queue of tasks. Tasks can be submitted to the tasks queue and as soon As one of the worker threads which belongs to the pool is idle it will take the next task in the queue and execute it. When finished, the thread will resume monitoring the tasks queue for more tasks.

The java library contains a ready-made threadpool implementation called ExecutionService. An ExecutorService is a class that internally manages one or more threads and allows you to assign tasks for them. There are many types of Executor services (each of them with a different policy regarding how to manage the internal threads – how many tasks should be performed at the same time, etc), but all of them implement the ExecutorService interface.

In the following example we use an executor service which has a fixed number of threads:

static double[] paraRowSum2(double[][] matrix) throws InterruptedException {

double[] vector = new double[matrix.length];

ExecutorService threadPool = Executors.newFixedThreadPool(4); //4 threads only

for (int i = 0; i < matrix.length; i++) {

int fi = i; //an effectively final version of i

threadPool.execute(() -> { //add a runnable to the internal tasks queue

for (double v : matrix[fi]) {

vector[fi] += v;

}

});

}

threadPool.shutdown(); //don't accept more tasks, terminate workers once the last task completed

while (!threadPool.isTerminated()) { //the following is similar to Thread.join

threadPool.awaitTermination(1, TimeUnit.DAYS);

}

return vector;

}

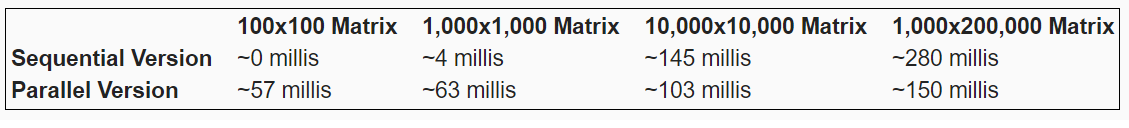

How our parallel execution performs now? Tested on the same machine as in the previous test we received:

We should notice right ahead that for small matrices - the sequential execution was faster, why is that?? The reason that executions with small metrixes took more time (relatively to the sequential version) is that for each task that we submitting to the queue, the executor service must wake up one of the sleeping threads, make sure that only one thread receive the task (synchronization), the thread need to execute the task and then recheck the queue - this takes time. If the tasks that the thread receives are small relatively to the time that is taken for the task queue and threads management then we will get a bad performance.

Knowing what you know now, you can do any of the following in order to improve the performance of this code:

- Create a new method

mixedRowSumwhich first check the matrix size and then decide if calling the sequential or the parallel version - In the parallel version - you can first check the matrix size and then set the size of the thread pool based on that size.

- In the parallel version - in cases where the row size is small, you can compose tasks that sums more than one row each

-

A register is a small cell of very fast memory located physically inside the CPU. Registers are the fastest type of memory, in contract to the slower RAM main memory, located outside of the CPU. ↩

-

As noted above, only one execution unit can be executed by a given CPU at any given time. As a result, different threads in the same process cannot in effect be executed concurrently. We also need to review scheduling in a more fine-grained level; the scheduler selects not only the new process to be executed, but also the thread inside this process as well. ↩

-

When performing a context switch between threads in the same process, not all steps of a regular context switch need to be taken. For example, there is no need to restore any context of the process (but just to switch stacks) and no need to flush the CPU cache, as threads in the same process share their memory. ↩